Crestview Hills mother Karen Ruf speaks about the loss of her son J.C. Ruf to teen suicide in October 2016.

Sam Greene/The Enquirer

J.C.

Ruf, 16, was a Cincinnati-area pitcher who died by suicide in the

laundry room of his house. Tayler Schmid, 17, was an avid pilot and

hiker who chose the family garage in upstate New York. Josh Anderson,

17, of Vienna, Va., was a football player who killed himself the day

before a school disciplinary hearing.

The young

men were as different as the areas of the country where they lived. But

they shared one thing in common: A despair so deep they thought suicide

was the only way out.

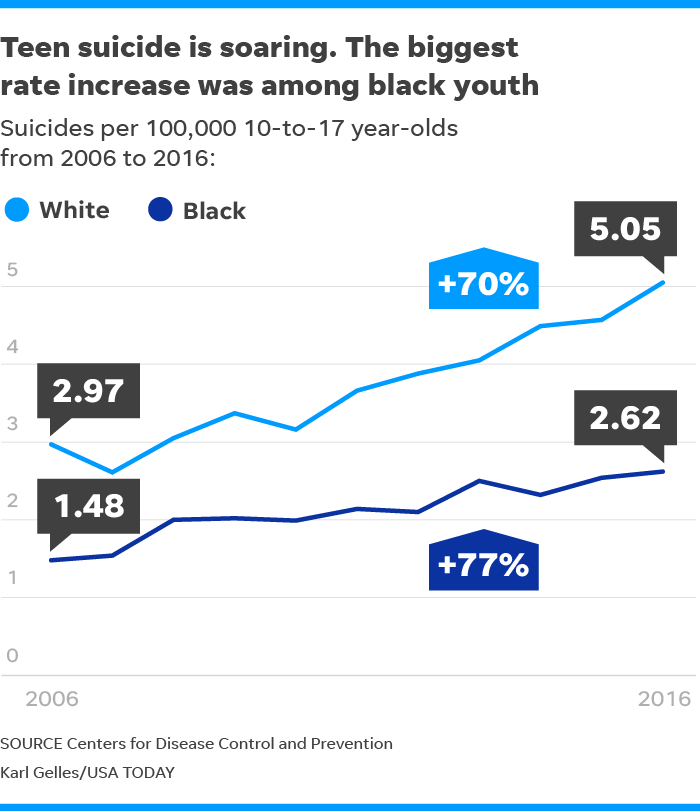

The suicide rate for white

children and teens between 10 and 17 was up 70% between 2006 and 2016,

the latest data analysis available from the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention. Although black children and teens kill themselves less

often than white youth do, the rate of increase was higher — 77%.

A

study of pediatric hospitals released last May found admissions of

patients ages 5 to 17 for suicidal thoughts and actions more than

doubled from 2008 to 2015. The group at highest risk for suicide are

white males between 14 and 21.

Experts and teens

cite myriad reasons, including spotty mental health screening, poor

access to mental health services and resistance among young men and

people of color to admit they have a problem and seek care. Then there's

the host of well-documented and hard to solve societal issues,

including opioid-addicted parents, a polarized political environment and

poverty that persists in many areas despite a near-record-low

unemployment rate.

And while some adults can tune out the constant scroll of depressing social media posts, it is the rare teen who even tries.

Then there's the simple fact they are teens.

"With

this population, it's the perfect storm for life to be extra

difficult," says Lauren Anderson, executive director of the Josh

Anderson Foundation in Vienna, Va., named after her 17-year-old brother

who killed himself in 2009. "Based on the development of the brain, they

are more inclined to risky behavior, to decide in that moment."

That's

very different from how even a depressed adult might weigh the

downsides of a decision like suicide, especially how it will likely

affect those left behind. And sometimes life is so traumatic, suicide

just seems like the best option for a young person.

Carmen

Garner, 40, used to walk across busy streets near his home in

Springfield, Mass. when he was a teen, hoping to get hit by a car to

escape life with drug addicted parents.

"Our

students are dying because they are not equipped to handle situations

created by adults — situations that leave a child feeling abandoned and

with a broken heart," says Garner, now a Washington elementary school art teacher and author. "Our students today face the same obstacles I faced 30 years ago."

After the leaves fall

November

is an especially difficult time in the Adirondack mountains resort town

where her family lives, says Laurie Schmid, Tayler's mother. As the

seasons change, the trees are bare, it's bitter cold and the small

community has shrunk after summer residents leave their lakefront

cottages.

In the weeks before he took his life

the day before Thanksgiving 2014, Tayler seemed sullen but his family

chalked it up to "teenage angst and boredom and laziness." It was likely

"masking his depression he was dealing with the last few years of his

life," she says.

As

her son moved through his teenage years, Schmid says she became less

focused on getting her son in to see his pediatrician annually, because

he didn't need shots and wasn't as comfortable with a female doctor.

Besides, he got annual physicals at school to compete on the school

soccer and track teams. Among the "what ifs" that plague her now is the

question of whether the primary care doctor who had treated Tayler all

his life would have picked up on cues about possible depression a new

doctor missed.

She

had even tried to get Tayler to see a mental health counselor, even

though finding one in their area of upstate New York wasn't easy. Once

Schmid and husband Hans settled on one, Tayler refused to go.

One

positive has risen out of the pain. There are far more resources and

awareness about mental health and the need for counseling in her area

now, thanks in part to the family's advocacy through the "Eskimo Strong"

group it started. A local counseling center even has an office at the

high school now.

Schmid

speaks to schools and parents regarding signs of depression, to

encourage counseling, and provide information for suicide hotlines and

text lines. Her oft-repeated motto is "Say Something" and "Talk to

Someone."

Mental illness also needs to be covered

by insurance at the same level as physical illness, says psychiatrist

Joe Parks, Missouri's former medical director for mental health

services.

There need to be more psychiatrists and

they also need to be part of primary care clinics, Parks said. At his

community health center in Columbia, Mo., he screens those who may be

suicidal and taught others to do it, too. Such "accountable care" was

envisioned, but not fully realized, under the Affordable Care Act.

Children

and teens who aren't covered by their parents' insurance can at least

rely on Medicaid's Children's Health Insurance Program. That's hampered

by low reimbursement rates that mean few psychiatrists accept it,

however.

So, even children who receive mental

health treatment, Parks said, may be in environments dominated by family

members with drug, alcohol or domestic abuse issues.

"Wouldn’t you expect that to increase depression in children?" he says.

Suicide chic?

If

super skinny — or muscular — models aren't enough to depress a teen,

flipping through social media feeds can prove misery loves at least

digital company.

Teens regularly post about hating

their lives and wanting to kill themselves, so much in fact that Parks

says it's almost like a competitive "race to the bottom."

On

one hand social media provides a place to vent and get advice, but on

the other hand, as Anderson said, “if everyone is commiserating over

everyone, is it really helpful?"

Because teens

are interacting in a way that isn't face to face, there’s less of a

connection, so it’s hard to understand what, if anything, to say when

someone says they want to die. Teens say they will see a post about

depression or suicide ideation and sometimes just pass it off as

relatable dark humor.

A recent post in one

Baltimore teen's Facebook feed: "Alright, so I will literally pay anyone

to shoot me in the head. Who wants a go at it? Please."

She included a smiley face emoji.

Blacks do kill themselves

Two African American preteen Washington charter school students killed themselves in the space of about two months recently, drawing attention to something not commonly thought of as a problem.

"There’s

been a lot of discussion about how suicide is potentially thought of as

a white person’s issue," says Craig Martin, global director of mental

health and suicide prevention at the men's health charity Movember

Foundation. "As a result of that, less is being done in black

communities to look at the issue of depression."

More:

There's

also a more pronounced stigma in the African American community

surrounding mental health issues. African American men have fewer mental

health issues but more serious types when they are present. And they are far less likely to seek treatment, says New York City psychiatrist Sidney Hankerson.

Then there's the trauma that comes with living amidst multi-generational poverty and addiction.

A

version of the much-publicized opioid epidemic in often-rural white

communities has plagued inner city black families since long before

Garner was a boy.

Garner

thought "normal" meant watching his mother shoot heroin and his aunts

and uncles smoke crack. "I lived with rapists, murderers and drug

dealers and gangsters," he said.

Now, his students are his motivation. They and his family remind "me I don't have to try to kill myself anymore," Garner says.

On

a Monday night, Karen Ruf went to a Bible study and J.C. took his

grandmother out for unlimited shrimp on a Red Lobster gift card. When he

got home, he talked to some friends at about 7:30 p.m. No one heard

anything different in J.C.’s voice. Karen returned around 9:15 p.m. to a

quiet house. She called for her son, no answer. She came downstairs and

found his body.

Ruf

knew J.C's death wasn’t an accident because her son left his phone

unlocked so she could find his note: “Everything has a time. I decided

not to wait for mine. They say we regret the things we do not do. I

regret it a lot.”

Schmid's son Tayler also left

something on his phone. A video suicide note that talked about the

depressive thoughts he was having.

Hans and Hansen Schmid watched it. Laurie says she hasn't been able to: "That's not how I want to remember him."

Contributing: Marquart Doty, Janiya Battle and Ashanea Parker of the Urban Health Media Project, which O'Donnell co-founded.

HOPELINE offers emotional support and resources - via text message -

in an effort to prevent suicide. Text “HOPELINE” to 741741.

Wochit

No comments:

Post a Comment